There are strong reasons to claim that the relationship between the U.S. dollar and the yellow metal is negative. As the academic researchers from Loyola New Orleans University, Christner and Dickle, found in this paper, the negative correlation between gold and USD/EUR, as well as between gold and USD/GBP, held in almost each year during the 1999-2011 period. Similar results were reached by Fergal O’Connor from the London Bullion Market Association and Dr. Brian Lucey from Trinity College Dublin. Instead of comparing two currencies, they conducted a more comprehensive analysis, using Trade Weighted Index (TWI)– a weighted average of exchange rates of a home and foreign currencies– with the weight for each foreign country equal to its share in trade with the home country (euro has 57.6% weight, Japanese yen 13.6%, while British pound sterling 11.9%). In this article they found that for most of the time from January 1975 and February 2012, the “correlation between the returns on gold expressed in a currency and the returns on the trade-weighted value of that currency is negative over 90% of the time for each currency”. In this article Noll Moriarty found a negative correlation between the U.S. dollar and gold, as well as between the dollar and all base metals. However, the World Gold Council in the fourth volume of Risk Management and Capital Preservation pointed out that gold has one of the strongest, just slightly lower than silver, inverse relationships with the US dollar, with the average correlation of approximately -0.4 to the US dollar from the 1970s to 2011. The negative relationship between the U.S. dollar and gold does not often occur on a daily or weekly basis, but is almost always seen in annual or longer trends.

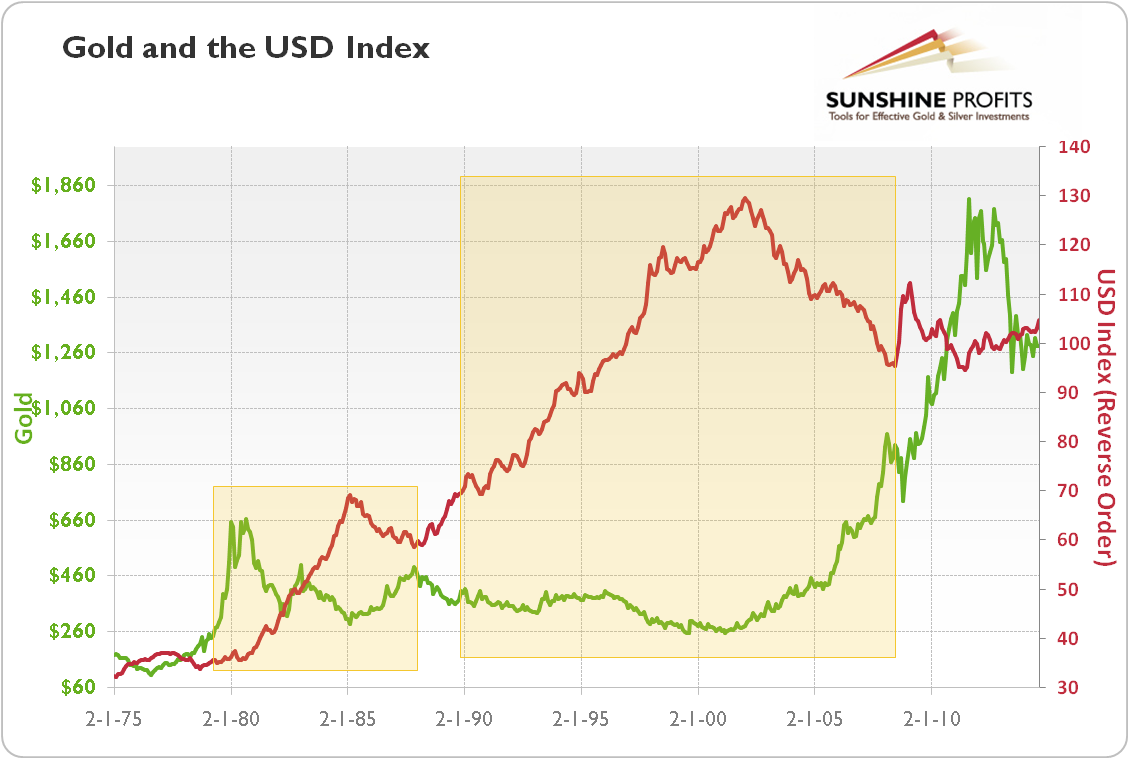

Just take a look at the chart, illustrating long-term co-movement between gold and dollar. The appreciation of the U.S. dollar from 1980 to 1985 was accompanied by a decline in gold prices, while strong depreciation in the U.S. dollar from 1985 to 1987 was associated with an increase in yellow metal price. Similarly, a period of rise in the U.S. Dollar Index from 1988 to 2002 coincided with declining or flat prices of gold, while the depreciation in the U.S. Dollar from 2002 to 2008 was accompanied by the bull market in gold.

Graph 1: Gold (green line) and US Dollar Index Trade Weighted (red line) from 1975 to 2014

Why does this correlation hold? The most intuitive and popular reason is that gold is generally quoted in US dollars, so any movements in the strength of the dollar will likely mirror the dollar price of gold: when the dollar rises, gold falls and vice versa. However, this explanation is a little too simplistic. Why does the depreciation in the U.S. dollar, which means lower real purchasing power in the hands of Americans, increase American demand for gold? Obviously, there is no automatic link. The proper argument goes along the line: as gold is traded primarily in dollars, a weaker dollar makes gold cheaper for other nations to purchase. So it is an increase in foreign demand that drives up the dollar price of gold and causes the negative relationship between gold and the U.S. dollar. This relationship will be easily understood if we realize that a significant part of demand for gold comes from outside the USA.

The second reason is that gold is a bet against the US dollar. Let’s analyze the anti-inflationary nature of gold first. Since many investors consider yellow metal as an inflation-hedge, if U.S. inflation accelerates at such a pace that it depreciates the dollar, gold gains. What is more, the U.S. dollar inflation increases mining costs, which tends to raise gold prices in the long-run. However the supply-side impact on gold is rather overstated by many analysts, who neglect the currency character of gold.

Gold is not really an inflation-hedge, or at least not always. The best proof may be the 1982-2002 period, when gold definitely did not guarantee the protection of capital. Another, perhaps even more illustrative example is the period from early 1980 until early 1985, when the price of gold lost about two thirds of its value from the peak to the bottom, while the price level rose by one-third. Why? The reason is very simple: the dollar appreciated by more than 90% in nominal terms and by 45% in real terms relative to the Deutsche mark, which caused the rise of the U.S. dollar by more than 50%.

Therefore, some analysts prefer to think of gold as a dollar or dollar-denominated-system hedge. These are not the same, as the period between 2002 and 2007 illustrates: the U.S. dollar index was falling (the dollar was losing its value compared to other currencies), while the bubble in dollar denominated assets, like real estate, was being created in the same time. We may say that gold is a hedge but against changes in the external purchasing power of the dollar rather than against changes in the internal or domestic purchasing power of the greenback. Its price is related more to the U.S. dollar index than to U.S. CPI (although changes in the inflation rate may affect the USD exchange rate).

In this perspective, movements in the gold price in U.S. dollars reflect confidence in this currency. When the trust in dollar or whole dollar-denominated-system falls, the price of gold rises and when the confidence in greenbacks is restored, the price of the yellow metal decreases. This is why gold was not gaining from the 1980s up to the 2000s, despite inflation: Volcker simply renewed trust in the U.S. dollar for the next 20 years. Undoubtedly, rising inflation may be one of the causes of the plummeting trust in dollar (as in the late 1970s). However, it is not always a cause of investors’ concerns – sometimes it may be liquidity crisis and deflation (like in 2008). In other words, gold moves inversely to the U.S. dollar because it is considered as an alternative currency, although the gold standard was finally abandoned in 1971. But the historical association of gold as the ultimate money is still deeply rooted in the minds of investors and central bankers (not without a cause: gold cannot be printed), which still makes it a hedge against the U.S. dollar.

Thirdly, as we have already mentioned, gold is both a commodity and a currency. Indeed, gold is traded continuously in a well-organized spot and futures markets with daily trading volumes comparable to major currency pairs such as the US dollar-pound sterling. It is also held as a reserve currency by the central banks. Therefore, if the U.S. dollar runs into trouble, investors (and central banks) can shift their reserves to other currencies, like the euro, yen, pound sterling, Swiss franc or… gold. Conversely, when the U.S. dollar goes up, investors (and central banks) may replace gold with greenbacks. In this scenario, gold is not considered as only a dollar-hedge, but rather as a hedge against all fiat currencies (among them U.S. dollar). This is an important property of this metal, because it can actually explain why a negative relationship between the U.S. dollar and the yellow metal does not always hold.

Would you like to know how? We analyze this issue in our monthly Market Overview reports. We provide also Gold & Silver Trading Alerts for traders interested more in the short-term implications of the relationship between the gold and U.S. dollar. Sign up for our gold newsletter and stay up-to-date. It's free and you can unsubscribe anytime.

Thank you.

Arkadiusz Sieron

Sunshine Profits‘ Market Overview Editor